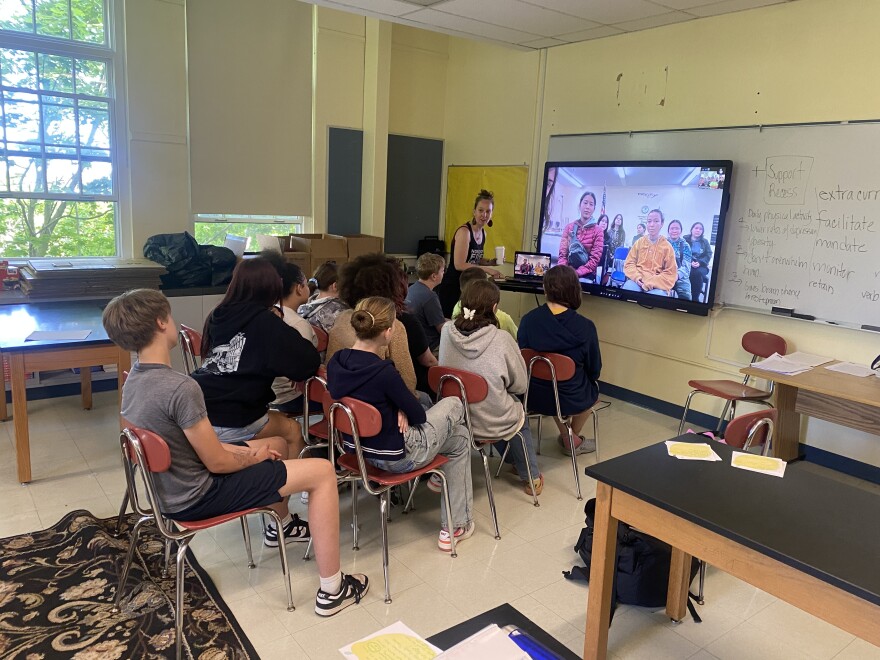

In a classroom at the Provincetown International Baccalaureate (IB) Schools in Massachusetts, a group of middle school students squished together for a video call with their pen pals from Mertarvik, Alaska.

“How is erosion affecting your life?” asked Mertarvik junior Jojean George through the screen in Alaska.

Twelve-year-old John Gunn in Provincetown didn’t have to think much before responding — it’s a topic he knows a lot about.

“Over time, Provincetown will eventually become an island,” Gunn explained. “Because that part that connects us is slowly narrowing because of the wind moving on the sand and the waves.”

Provincetown is the very last community on the hook-shaped peninsula of Cape Cod in Massachusetts, just about as far away from Western Alaska as you can get in the United States. The seaside community of 3,000 can swell to triple that in the summer months, attracting visitors to its vibrant art scene and proud LGBTQ+ community.

The pen pal project was created by Provincetown-based photojournalist Emily Schiffer and Alaska-based creator Katie Basile. The project aimed to foster connections between kids in places facing coastal erosion, and was funded by the organization Anonymous Was a Woman in partnership with The New York Foundation for the Arts. Both instructors taught the students photography skills, allowing them to document their home communities and respond to their pen pal letters visually as well as in writing.

Finding common ground

Provincetown faces coastal erosion and increased flooding because of climate change. It’s something their pen pals can understand.

The Alaska students are originally from the village of Newtok, a place that no longer really exists. The Bering Sea coastal village steadily deteriorated due to permafrost thaw. The ground sank and the Ningliq River washed away 70 feet of shoreline each year. In October, after a tribal council vote, the last residents of Newtok relocated to Mertarvik.

Each group of students have learned a lot about the other in their exchanges of emails, photos, and Zoom calls. The Provincetown class wondered in their letters how moving solved the erosion problem for the Alaska village, asking about what made Mertarvik safer than Newtok.

“I remember the answer, which was that Newtok was very flat on the ground,” Gunn explained. “It was kind of, like, elevated, but it was still pretty flat. But Mertarvik is on, like, they said it's, like, these rolling hills.”

Mertarvik is also more stable because it’s built on rock instead of permafrost and dirt. This is something the Provincetown kids can grasp pretty well because their community is built on sand.

Stories of relocation

Provincetown’s own history is rooted in a story of relocation.

Thirteen-year-old Bella Wertwein knows this story well. She said that when the Mayflower landed in what would become the United States, colonists settled in a place where they couldn’t grow food, and so they had to move.

“And so they floated all of their houses over,” Wertwein explained.

She sits on the beach by her old house, looking out at the wide Atlantic Ocean. The wooden house she lived in was one of the ones floated across an ocean inlet in the 1850s — nearly 200 years ago.

“And they used to say the bay was so calm that the housewives could cook a meal in the kitchen while they were coming across,” Wertwein said.

Now the community of Provincetown faces existential threats from the ocean. Since 2018, coastal flooding during winter storms has become more frequent. City management said that the town is now looking, in part, at a vertical relocation to survive, with owners of coastline houses raising their homes on stilts if they can afford it.

Being a kid in Provincetown involves pier jumping after sailing camp, sand dune sledding when there’s snow, and grappling with the tangibility of a changing climate. Bella said that means sometimes going to school prepared for a disaster.

“If I went to school on a day that we had been flooded, or a weekend, or flooding is happening, I would wear two pairs of pants, two pairs of sweaters,” Wertwein said. “I would bring a kind of pack of clothes with me to school.”

During a winter storm in 2020, Wertwein’s old home flooded. She talked about returning home to a chaos of rugs and chairs strewn about and seaweed and ocean debris in the streets. It was right when she moved to Provincetown. Then the flooding kept happening.

“I was like, ‘Oh, we've done this before. We've done this before,’” Wertwein said. “But then it started getting, like, over and over and over and over again. So it was just, like, interfering, kind of, with like, day to day life.”

Eventually her family sold the house that was floated across the bay, but flooding is still something Wertwein said that she thinks about a lot. She’s been developing an idea for a breakwall barrier that could harness the power of storm waves. She said that climate change is something most kids her age don’t get in the same way, but the Mertarvik kids do.

“It makes me so happy talking to people who understand, like, climate change is happening,” Wertwein said. “Climate change is really bad, and we need to do something or bye-bye human civilization.”

Wertwein said that it’s made her connection with 17-year-old pen pal Glennesha Carl meaningful, like a mentorship.

“When they mentioned flooding, I thought about Newtok because Newtok is a place to flood all year long,” Carl said. “Like, every summer it floods. Every fall it floods.”

In her letters to Wertwein, Carl said that she wrote about Typhoon Merbok, about leaving her home in Newtok, and about returning last fall through the pen pal project to take pictures.

“Like, it was a wave of sadness, and as we got off the boat I could feel like it was my home, but not my home," Carl said.

Carl said that memories rushed back to her, like fishing with her friend in the pond behind her old house.

“There's no more pond. There's no more fish, like that's a whole new environment,” Carl said.

In their correspondence, the two groups also wrote about their favorite music and what they like to do for fun. It’s a kid-woven tapestry of Billie Eillish, squid and salmon fishing, and coastal erosion.

Earlier in 2025, their stories as kids impacted by climate change got to live beyond their own inboxes. The students’ letters and photos were selected for display at a photography exhibition in New York City. Both groups of students traveled to the Big Apple to meet in person for the first time.